Friday, December 30, 2011

Statins and Prostate Cancer

The researchers found that men who died of prostate cancer were half as likely to have taken a statin at any time, and for any duration, than men in the "control" group. Those with fatal cancers were 63 percent less likely to have ever taken a statin, according to findings published in Cancer.

I would love for statins to reduce the risk of prostate cancer. Readers of this blog know I am relatively pro-statin, in the right patient population. However, this study is too limited to make an actual connection, and I would not recommend taking statins solely for prostate cancer prevention.

What did the researchers do? The looked at the medical records of 380 men who died of prostate cancer and matched them with the records of another 380 men who did not have prostate cancer. They use statistical techniques to adjust for difference such as age, weight and other medications.

What's the problem with the study? First, if the study findings are correct, such a study that uses medical records and then looks back in time can not prove causation. It only proves association. This means that the study doesn't prove that taking a statin will ward off prostate cancer. Rather, the results mean that men who had died of prostate cancer were less likely to take a statin. This is a big difference. There are multiple examples where a confirmed association did not result into a confirmed causation (Vitamin E/C and Folic Acid for preventing heart attacks). In addition, there are many reasons that the association is in fact not correct. Perhaps men who had been diagnosed with prostate cancer chose not to take statins, even if their doctors recommended it, because they were more concerned about the prostate cancer? Perhaps men who did not have prostate cancer were extremely health conscious and were more aggressive about both doing things to prevent cancer (exercise, diet, etc.) as well as being more aggressive about taking statin medications for high cholesterol?

Why this might be true? The only way to truly determine causation is to perform a randomized clinical trial (RCT). Only a RCT can both eliminate some of the confounding variables (i.e. were the men without prostate cancer more aggressive about their overall health) and demonstrate the primary ingredient for causation: that exposure always precedes the outcome. If factor "A" is believed to cause a disease, then it is clear that factor "A" must necessarily always precede the occurrence of the disease.

However, there are two findings from this study that support causation. First, is dose-response relationship. Only the newer, more potent statins showed benefit. Taking a lower potency statin was not protective. The second is biologic plausibility. According to the Reuters report, Dr. Stephen Freedland, who studies prostate cancer at the Duke University Medical Center in Durham, but wasn't involved in the new study was quoted as stating that statins may protect against fatal prostate cancer through their known cholesterol-lowering effects, mentioning that cholesterol is a "key nutrient" for cancer cells, so lower cholesterol levels in the body could prevent more aggressive forms of cancer from developing.

Bottom Line: This study is exciting and will hopefully lead to randomized trials which can prove whether or not taking a statin will prevent prostate cancer. For now, there is very limited evidence to suggest this would actually work, and men should not start taking a statin just to lower their risk of prostate cancer.

Wednesday, December 7, 2011

More Evidence that Lantus Causes Cancer

I have previously blogged about this back in 2009 when the first reports surfaced about the link between Lantus and cancer. (See A New Problem With Insulin: Cancer , Lantus Causes Cancer! Why Doesn't Anyone Seem Care? and Lantus and Cancer- A Closer Look Is Not Reassuring )

Back in 2009, when the story broke, the FDA acknowledged the potential link but stated that the data was insufficient and recommended that patients not stop taking Lantus, at least without discussing this with their physicians. They stated that they were "currently reviewing many sources of safety data for Lantus, including these newly published observational studies, data from all completed controlled clinical trials, and information about ongoing controlled clinical trials, to better understand the risk, if any, for cancer associated with use of Lantus." However, we didn't hear much until January, 2011 when they released an update declaring that they had reviewed the four 2009 studies and has "determined that the evidence presented in the studies is inconclusive", and in addition had reviewed results from a 5 year study (sponsored by the makers of Lantus) which did not show an increased risk but was "not specifically designed to evaluate cancer outcomes," concluding, "at this time, FDA has not concluded that Lantus increases the risk of cancer. Our review is ongoing, including review of information from a current clinical trial." With the new study reported today, it will be interesting to see whether the FDA chooses to give and update or reveals and additional information, such as a VA data set they are supposed to be evaluating.

According to the Bloomberg article, a Sanofi study from Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark and Scotland is complete and will be submitted to health authorities this month. In addition, U.S. study will be finished in early 2012, while a final report from Europe will come later. All of these studies combined will involve more than a million patients, which will hopefully be enough to give a more conclusive answer.

To be clear, I am not 100% convinced that Lantus causes cancer. However, there is another long acting insulin (Levemir) which has similar efficacy to Lantus, has not been associated with cancer, and has a substantially different affinity for the insulin like growth factor (IGF) receptors that are implicated in the possible connection. Given the mounting evidence of a cancer link with an equally effective product that appears to be safer, I can't see any reason to prescribe Lantus when Levemir is available.

Monday, October 24, 2011

Industry Funded Studies

One email I received from a reader had to do with industry funded studies. This is not an uncommon concern, and one that frequently shows up on this blog and others. The email encapsulates many people's concerns with industry funded studies.

Dear Dr. Mintz,

I am staring at my computer unable to formulate the words to express my opinion on a very important subject. I do not want to come across as rude, condemning or complaining, yet I am compelled to share with the medical community my honest patient perspective.

I view the medical profession as one of the most respected on earth. But it isn't perfect. As a patient I become very discouraged when I see a medical professional look towards industry funded drug studies to make medical decisions.

Now for the painfully honest part. When I see a Doctor subscribe to "results" from an industry funded drug study, my image of that physician goes to pot in a heartbeat. "How can he/she be so gullible" and "Incompetent" are thoughts that pass through my mind. I quickly lose trust in that physician's ability to make smart decisions in my health care, and the doctor loses my business.

On on the contrary, I asked a physician what he thought about industry funded drug studies, he answered "I ignore them." This doctor won me over in three words.

Obviously it takes excellent academic ability to become a physician, but I look for more than that. I look for wisdom and integrity when choosing a physician.

There is no question that industry studies are biased by nature. The drug company is beholden to its stockholders to increase sales. Therefore, they have a fiduciary obligation to make sure that their research puts their products in the best light. This is not unlike any product in the US where a manufacturer does research stating that people prefer it or it works better than a competitor. Unlike these products, medications are heavily regulated in the United States. Thus, for a medication to get approval or to make any claims, all studies, including ones funded by the industry have to go through the FDA.

Here's the real problem:

Almost all research done on medications is funded by the industry. I would love it if instead of relying on industry sponsored studies, I could rely on non-biased information. However, when it comes to medications, these studies are few and far between. In 2005, the industry spent close to $40 billion dollars on research. Compare this to the entire NIH budget that same year of less than $30 billion. Also, understand that the NIH spends very little money on actual drug studies. They focus more on finding a cure to cancer, not whether expensive medicine X is just as good as the older generic medication.

When I want to know whether to buy product X vs. product Y, I can go to an independent source such as Consumer Reports, which does their own, independent research. There is really no such independent source for drug information. In fact, prescription drugs is one of the only areas that Consumer Reports does not do their own research. All their recommendations on which medicine is "right for you" come from drug company sponsored studies.

If we ignored all industry funded studies, we be ignoring most of the data. In addition, since these studies are heavily regulated, we would be ignoring mainly good, helpful data, even if biased. The simple alternative is to fund the NIH or similar organization equally to the drug companies in order to do independent research. Of course this would likely require significant government spending, which is likely a non-starter.

The good news is that independent comparisons of treatment, called comparative effective research, are starting to be done, and (whether you like health care reform or not), there is funding for this research in the Affordable Care Act. Unfortunately, this funding is not nearly enough to compete with the drug companies. Thus, unless you are willing to pay considerably more in taxes or drop some needed services, physicians and patients still need to rely on industry funded research. Many studies from the industry are actually quite good and useful, though, because of inherent bias, should always be looked at with a skeptical eye.

Sunday, October 9, 2011

PSA: To Screen or Not to Screen

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

Is meaningful use the right incentive to get physician's to use EMR's?

As this related to Electronic Medical Records (EMR's), achieving meaningful use is not easy. The technology for clinical decision support (a requirement) is not quite ready for prime time. Nor is there an easy way to share parts of the EMR with patients. In a study of almost 600 docs who had been using EMR's, most were confident that they would qualify for meaningful use and get bonuses for doing so. However, the survey also found that the majority of these physicians would not meet some of the criteria. Thus, though the financial incentive seems nice, the path to getting these incentive may be so unattainable that physicians won't waste the effort or expense.

More importantly, some of the "stuff" that's meaningful in meaningful use, may not have value for physicians. Policy makers that developed these criteria were understandably thinking on a population level (lowering blood sugar in a population of diabetics). However, physicians are used to dealing with patients one on one.

A recent survey of EMR using physicians was done over at Software Advice regarding the advantages of using EMR's. Granted 50 respondents may not accurately generalize to most physicians; however, some of the results are telling. What do doctors like about EMR's? Greater accessibility of charts, easier to read notes, more accurate patient information, and improved coordination of care by having the ability to share data. As a user of EMR's for well over a decade, I would concur with these findings. EMR's are far from perfect, but based on these advantages, I could never go back to paper. What "benefits" of EMR's did doctors not see as readily? Improving preventative care, opportunity to participate in pay for performance, improving clinical decision making, and reducing errors/improving patient safety.

Thus, under the current plan to increase EMR use by physicians, the financial incentives may be too hard to achieve and the purported benefits may not be easily perceived. This combination does not bode well for the adoption of EMR's by most physicians. Instead, policy makers might want to consider a different approach. First, rather than create a financial carrot that will be too difficult to achieve for most, use that money to reduce barriers to adopting EMR's in the first place. Second, instead of focusing on the benefits important to policy makers, focus on benefits that are important to physicians, such as making our work easier and more productive. This is important because EMR vendors design their products on what they believe will meet their customer's needs. The first EMR platforms focused on improvements in billing and coding to capture more revenue. Now, vendors are focused on helping physicians achieve meaningful use. If vendors focused on making a physicians work easier and more productive (and policy maker made it easier to adopt these tools), EMR adoption would be much greater than it is now.

Friday, September 2, 2011

Disappointing Results for Crestor

As reported in Pharmalot's post Disappointing Crestor Results For AstraZeneca (see the official AstraZeneca statement here ), the just released results of SATURN show that the 40mg dose of Crestor was numerically but not statistically significantly better and reducing plaque build up (as measured by % change) as the 80mg dose of Lipitor. As secondary measure, plaque buildup as measured by volume was statistically significant, but since this was not the primary outcome of the study, it is likely enough for insurers to give Crestor a favorable status on their formulary lists.

Bottom Line: Crestor is a great drug. It reduces LDL better than Lipitor. We know that from outcome studies of all statins, that the lower the LDL with a statin, the more you decrease heart attacks and strokes. In addition, despite it's potency, it has very good tolerability. Certain patients that might need 80mg of Lipitor, might not be able to tolerate side effects at that high of a dose, and might end up doing better on 20mg or 40mg of Crestor. That said, starting in 2012, unless AZ cuts the price on Crestor drastically, it may be a challenge to get the prescription approved for patients.

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

All In For Crestor

Another very important study will also be presented that same November 15th, 2011: Comparison of the Progression of Coronary Atherosclerosis for Two High Efficacy Statin Regimens with Different HDL Effects: SATURN Study Results. The SATURN study is the Astra Zeneca (makers of Crestor) study comparing high dose Crestor (40mg) with high dose Lipitor (80mg).

Patients in the SATURN study will have known cardiac disease as indicated by a need for coronary angiography (angiogram) and angiographic evidence of coronary disease. The main end point is is IVUS-assessed change in the percent atheroma volume in a >40-mm segment of a single coronary artery; which is a "doctor" way of saying they are going to look for plaque build up in the artery. This is the same end point used in the famous (or infamous) ENHANCE trial which showed that adding Zetia to simvastatin (zetia + simvastatin = Vytorin) did absolutely nothing to plaque build up ( Vytorin and Zetia: What to do now? )

What's interesting about SATURN is that the LDL lowering properties of the highest doses of Crestor and Lipitor are about the same. However, at those doses Crestor raises the HDL or good cholesterol by about 8% where Lipitor only raises HDL by 3%. Other studies have shown that plaque build up in the arteries (atherosclerosis) that causes heart attacks and strokes, is not just about LDL, but also about HDL. Other studies looking at high doses of Crestor when compared to placebo show that it can prevent plaque build up and possibly even lead to regression. The Lipitor data on this is less robust.

The timing of the results at the AHA is particularly interesting, since it will coincide with Lipitor going generic. Zocor or simvastatin has been generic for a while, and works well in many patients. However, patients requiring more aggressive reduction in their cholesterol will not meet their goals on simvastatin and high dose simvastatin is associated with side effects, which prompted a recent FDA warning. (See Don't Take High Dose Simvastatin). Thus, the need for a generic potent statin like Lipitor is huge. However, this could mean that insurers will make it very, very difficult for patients to get Crestor. UNLESS......... SATURN proves that high dose Crestor compared to high dose Lipitor significant reduces plaque build up in high risk patients.

Therefore, the SATURN trial is really a huge gamble for Astra Zeneca. When Merck's ENHANCE trial showed that Vytorin didn't really do more than the generic statin, prescribing rates dropped precipitously. Crestor likely faces the same fate is SATURN turns out to be a negative study.

Thursday, August 4, 2011

Why OTC Lipitor is a Bad Idea

Readers of this blog know that I am a big proponent of cholesterol lowering medications like Lipitor (statins) for patients at moderate to high risk of cardiovascular disease. In particular, I am a fan of the more potent statins like Lipitor and Crestor, because of their increased efficacy with fewer side effects (see Don't Take High Dose Simvastatin). Finally having a generic version available of Lipitor will be a great thing for many patients.

That said, making Lipitor OTC is a bad move. First, there is a difference between medications like Prilosec and Claritin that have gone over the counter and Lipitor. Diagnosis for GERD and allergic rhinitis for which those medications respectively treat are made mostly on symptoms alone. Patients don't need to go to medical school to suspect that they may suffer from heart burn or allergies. Starting treatment without seeing a physician is actually medically sound because more often then not the medications will relieve symptoms avoiding a physician office visit. In contrast, starting a patient on a statin is much more tricky. Patients need to know their individual risk for cardiovascular disease. Though there are tools available online to determine this (I use the NIH's risk calculator daily in my clinic), determining individual risk of disease, benefit of taking a medication and weighing this against potential side effects is best decided by a discussion between a doctor and patient. Secondly, before starting a statin medication, one needs to know their cholesterol levels. Though there are other methods (health fairs, work screenings) of determining cholesterol levels, getting a blood test usually requires a visit to the doctor's office. In addition, follow up blood work (checking for medication efficacy, liver side effects) is warranted after starting treatment. Thus, the benefit of having a medication OTC is negated. Finally, Claritin and Prilosec are very safe. They are as safe or safer then other OTC medications. Lipitor is also very safe, but is associated with rare, but serious side effects. Taking Lipitor OTC without consultation with a physician creates the risks of patients developing these side effects without proper warnings and therefore potentially worse outcomes if attention is not sought.

The second main reason that OTC Lipitor is a bad idea is that it will hurt more patients than it will help. The reason for this is that when a medication goes OTC, insurance companies usually will not pay for them. Now that Allegra is over the counter, it is virtually impossible for any of my patients to get a prescription version antihistamine. Though they can easily get this OTC, not having a prescription means they need to pay for it out of pocket. The cost of an OTC medication, even if the generic OTC version is used, is generally more than the co-pay for a generic prescription. It is unlikely that generic Lipitor will make the $4 Walmart or Target list, but after six month, the co-pay for generic Lipitor would still likely cost a lot less for most patients then paying for OTC Lipitor out-of-pocket.

Bottom Line: The reason why Pfizer wants Lipitor OTC is for one reason: to make more money. They can argue that cardiovascular disease is the number one killer in the US, and by having Lipitor OTC, it will be available to more patients. However, because statins require blood work and medical consultations, the risk of harm to patients outweighs the potential benefits of greater availability. In addition, this will result in cost-shifting to patients in order to boost Pfizer's profits. Hopefully, the FDA will say what they said when Merk tried to pull this off: "No."

Tuesday, July 5, 2011

Chantix should not be withdrawn.

Chantix is not without issues. The main side effect is nausea, which about 30% of users will get. It is usually mild and usually goes away, though a small percent of people will not tolerate this. The more recent concern with Chantix was exacerbations of neuropsychiatric symptoms: depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. These side effects were not seen in many of the initial studies, but in later on via reports by doctors and patients after the drug was on the market. This method is called post-market surveillance. Post-market surveillance is critical in determining drug safety, because rare but serious side effects may not be seen when you only study thousands not millions of patients. However, unlike RCT's , proving cause and effect can not be determined. In regards to psychiatric symptoms, in the original studies that the Pfizer submitted to the FDA, Chantix had few interactions and did not show any. However, because Pfizer compared Chantix to bupropion (the only other pill indicated for smoking cessation, but also used for depression), patients with mental illness were purposely excluded from the study. (See more about this in Where's the Good News about Chantix? and More FDA warnings should not be cause for worry.) In fact, since these warnings first appeared, further studies seem to indicate that just stopping smoking, not necessarily Chantix, can cause these problems. Furthermore, warnings were not just added to Chantix but also to bupropion. Regardless or whether symptoms like depression or even suicidal thoughts is linked to Chantix or stopping smoking, doctors and patients should be aware of this concern for any patient quitting tobacco.

Now we have a new concern regarding Chantix causing cardiovascular events. The initial concern was raised by the FDA in their review of a study of 700 patients with known cardiovascular disease randomized to Chantix or placebo. Though Chantix was far more effective in helping these patients with known heart disease quit tobacco, there was a small number of increased cardiovascular events, more in the Chantix group than placebo. The total number of events was 28 in the Chantix group vs. 17 in the placebo. The study was not designed to show whether or not this number was statistically significant (was really true), but the FDA added a warning to Chantix' label.

However, a new study raises questions about Chantix and people without heart disease. This is being blasted all over the media. The Wall Street Journal reports "Drug Tied to Heart Risks." The New York Times reports "Study Links Smoking Drug to Cardiovascular Problems." ABC News states "Chantix: Quit Smoking, But Risk Your Heart?" All of them have similar language to the ABC news site stating:

Study authors looked at 14 past studies of Chantix and found that overall, people on the drug had a 72 percent increased risk of being hospitalized with a heart attack or other serious heart problems when compared with those taking a placebo.

That seems pretty bad! Unless, of course, you look at the actual data. The new study is a meta-analysis of studies looking at patients on Chantix without cardiovascular disease. The study is from the Canadian Medical Association Journal. They looked at data from 14 RCT's 8216 participants. They found that Chantix was associated with a significantly increased risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events compared with placebo on 1.06% [52/4908] in varenicline group compared to 0.82% [27/3308] in placebo group. In other words, the absolute difference between Chantix and placebo is 0.24% or 24/10,000. This sounds a lot less scary than 72% increase (relative increase) being reported in the media. It is also very, very important to note that the technique used to derive these numbers is a statistical technique, a meta-analysis, which is not nearly as rigorous as an RCT. Meta-analysis are designed to ask questions, not to answer them. ( I have blogged previously about the pros and cons of meta-analysis). Furthermore, even patients without a history of cardiovascular disease who smoke, have a risk for cardiovascular disease, which is why they need to stop in the first place.

Bottom Line: One must always question 1) the results of a meta-analysis because it has many limitations and 2) any non-RCT, especially a meta-analysis, with a very small absolute risk (i.e. 0.24%) especially if the authors/journalists are trumpeting a large relative risk (i.e. 72%) and also 3) take into account the context of the situation, i.e. the single best agent we have available for the leading preventable cause of death in the United States, might possibly have an associated very small increase in heart disease in smokers that will likely have a much greater risk of heart disease if they don't stop smoking. While I agree more research is needed, and warnings about a possibly increased cardiovascular risk are not inappropriate, pulling Chantix from the market would be a huge mistake.

Friday, July 1, 2011

Paying For Your Time

"I decided to bill the doctor," she says. "If you waste my time, you've bought my time."

Farstad mailed an invoice to her doctor based on her own hourly wage, and eventually received a $100 check in the mail.

As mentioned, this story has received considerable attention. Over at the blog Survivor: Pediatrics , Brandon Betancourt humorously counters "Why not bill everybody that wastes our time?" including the movie theaters that make us sit through commercials and previews before the movie we came to see, or even Disney for waiting in those long lines.

However, the issue of why patients have to wait is an important one. Most patients recognize that emergencies do come up in medicine, which often causes doctors to run behind schedule. However, medical emergencies are not the main reason why patients spend long waits in doctor's waiting rooms. The answer can be found in a study published last year and discussed in the New York Times "Study Shows ‘Invisible’ Burden of Family Doctors." Primary care physicians do a lot more during their day than just see patients. However, they only get paid for seeing patients. The actual study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine measured exactly what a group of family physicians did in a given day.

Family doctors are paid mainly for each visit by patients to their offices, typically about $70 a visit. In the practice in Philadelphia covered by the study, each full-time doctor had an average of 18 patient visits a day.

But each doctor also made 24 telephone calls a day to patients, specialists and others. And every day, each doctor wrote 12 drug prescriptions, read 20 laboratory reports, examined 14 consultation reports from specialists, reviewed 11 X-ray and other imaging reports, and wrote and sent 17 e-mail messages interpreting test results, consulting with other doctors or advising patients.

All of this unpaid work takes an incredible amount of time. Also, assuming that the doctors were collecting 100% of their $70 per visit, at 18 visits a day, with 60% overhead (often more for doctors), the doctor only takes home about $120,000 a year in salary. Now that seems like a pretty good salary, and is certainly much more than most Americans make. However, it is far lower than many other professionals with equal or less training (lawyers, accountants, dentists, college professors, etc.) and also doesn't take into account the enormous debt that medical students accumulate (in some cases close to $200,000 at graduation, adding up to well over $1 million if paid over the course of a typical loan). This is why our medical students are not going into primary care.

All this work can't be done in a given day, and the doctor can't see fewer patients to squeeze in this work because it will lower her salary even further. Another way to put this is that the doctor's time is valuable too, but she isn't get paid for her time. The doctor is getting less than what's it worth from the insurance companies for actually seeing patients and getting nothing from insurance for anything that's not face to face.

Thus, the doctor who is trying to see too many patients in too little time while simultaneously trying to get all the phone calls, lab results, etc. is going to run late. In my practice, with the exception of the first patient of a morning or afternoon session, I start each patient conversation with, "I am so sorry to keep you waiting." There is only so much that can be accomplished in 15 minutes. Primary care physicians who need to manage multiple complex medical issues have a choice: be good or be on time. I choose to do the best job I can, which causes most of my patients to wait much longer than any of them should.

One solution to the problem is to have insurers properly reimburse primary care physicians for all the work that they do. Unfortunately, regardless of who gets elected in 2012, this seems unlikely to happen. Another solution is to get the insurance companies out of the mix all together. This alternative solution is already starting to happen. Retainer or concierge practices, which charge an annual fee (on average $1500/year) allowing doctors to have a very small number of patients who have instant access and no wait times, are gaining in popularity. Some have suggested that this is one solution for the primary care crisis.

However, many patients can not afford high retainer fees nor necessarily need this level or service. For these patients, another solution is direct access primary care. Direct access primary care works more like a gym membership, where you pay a monthly fee for all of your basic primary care needs. You can use your direct access primary care provider as little or as much as needed. Qliance in Seattle, charges about $75/month.

There are a variety of other models that improve patient and physician satisfaction, and likely the actual quality of care. However, the key ingredient in all of these models is cutting out the insurance companies to save money, hassle and overhead costs; and collecting money directly from patients to enhance revenue. This combination allows primary care physicians to spend more time with patients, have increased access, and subsequently low to no waiting for patients.

Bottom Line: The current insurance based system keeps primary care physicians on a treadmill, usually forcing them to choose quality of care over patient convenience. Though all patients deserve high quality, patient centered care that is convenient as well, the solution of higher reimbursements and decreased hassles for primary care physicians does not appear to be happening any time soon. Thus, as a patient, you have a choice. If your time is valuable, then you are going to have to pay extra for primary care services. If you choose to (or are only able to) rely on health insurance premiums and co-pays to cover the cost of your care, you should expect to wait. Expect to wait to get a timely appointment with your doctor. Expect to wait for the phone call with results of your recent tests. And, of course, expect to wait in your doctor's waiting room.

Saturday, June 11, 2011

Actos Causes Bladder Cancer. Maybe We Should Have Kept Avandia?

Despite the many things you have heard about Avandia, back in July 2010, the FDA decided to severely restrict the use of Avandia for three reasons:

1. Despite limited and conflicting data, there seemed to be a signal of myocardial infarction for patients taking Avandia.

2. The one study proving Avandia's safety, RECORD (see here for more details) was discredited by FDA scientists due to potential reporting errors.

3. The advisers on the panel felt strongly that despite limited and conflicting evidence, the signal was enough to be concerned AND because Actos (similar drug in same class) did not seem to show this signal, why would doctors ever want to prescribe Avandia?

I have blogged extensively about Nissen's meta-analysis that triggered the whole Avandia scare. Meta-analysis have major limitations. Another group of researchers using the same data as Nissen's with different statistical techniques concluded that Avandia did not cause heart attacks. Large, randomized trials are the only way to determine certainty, and all available large trials (DREAM, ADOPT, ACCORD, etc.) with rosiglitazone showed no heart attack risk. As mentioned above, the one study designed to definitively show whether or not Avandia led to cardiovascular risk (RECORD, which showed that Avandia did not cause cardiovascular risk, and in fact surpasses the FDA's standard for cardiovascular safety) was harshly criticized by those within the FDA that wanted to see Avandia pulled from the market. Specifically, the FDA found that GSK had some errors in reporting the results of RECORD. Though these types of errors are not uncommon in very large trials, and likely won't affect the overall results of the study, nonetheless, the deserve looking into. However, the FDA promised to do a complete independent analysis of the RECORD results; a promise it has yet to deliver on.

The main issue here is #3: Actos appears to be safe, so let's dump Avandia. (Interestingly, independent cardiologists analyzed all the data and did not find a conclusive difference in cardiovascular risk between Actos and Avandia). Here is the full transcript of the advisory board. Since it is a very difficult document to read through, I have pasted some of the direct quotes below from some of the advisers who voted to either remove Avandia from the market or severely restrict its use. Based on these quotes, I feel pretty strongly that had the advisers known about Actos' bladder cancer risk, that they may have voted very, very differently. However, the FDA did know about the association between Actos and bladder cancer. They just chose not to mention it! In fact, when one adviser brought up the question at the July advisory board, the FDA only briefly mentioned this and discussed it more as a class effect also seen with dual PPAR agonists.

Avandia and Actos help diabetics use their own insulin better by hitting a receptor called PPAR. There are three main PPAR receptors: Alpha, Gamma and Delta. We don't know a whole lot about delta, but PPAR Gamma works on glucose, and PPAR alpha affects cholesterol. Fibrates like gemfibrozil, which lower triglycerides and raise HDL or good cholesterol are PPAR alpha agonists. Dual PPAR agonists were drugs that pharma were trying to develop that hit both alpha and gamma in order to help both with lipids and glucose. They have not been able to make it to market due to safety concerns (raised by, guess who??? Dr. Nissen). One of the differences between Actos and Avandia, is that Actos has a higher affinity for the PPAR alpha receptor, which is why it likely does a better job on raising HDL and lowering triglycerides than Avandia. Some have hypothesized that this might be the reason why Actos might not have the same cardiovascular issues as Avandia (though this has yet to be shown). If in fact, as stated during the FDA meeting (I am not aware that this data is published) that the bladder cancer risk was seen in both Actos and the dual PPAR agonists. Bladder cancer has not been seen with Avandia. In other words, the evidence (both available and suggested by FDA quotes that are public record) suggest that Actos may have more of a bladder cancer risk than Avandia.

Why the FDA in discussing to keep Avandia on the market would not extensively discuss the concerns of bladder cancer with Actos, paired with the weak and controversial data showing Avandia's cardiovascular risk and effort to discredit GSK's study proving Avandia's safety leads me to believe that the FDA's attack on Avandia was very much politically motivated. Scientists look at all the available data and weigh the risks and benefits of all options before making a conclusion. It is clear to me that the FDA's decision on severely restricting Avandia was more political then science. Based on the currently available data which now include bladder cancer risk, Avandia may actually be a better choice than Actos, but the FDA's restriction will essentially prevent any doctor from being able to prescribe Avandia after November.

Select quotes from advisers who voted to voted to either remove Avandia from the market or severely restrict its use:

DR. SCHAMBELAN: This is Morrie Schambelan. I voted E. (remove Avandia from the market) . I was one of the brain-dead kangaroos last time (meeting in 2007) who was on the fence, largely because I did see a signal for harm. I was led at that time by the comparison to active comparators, which I think is much more relevant to me than placebo. I wasn't swayed by the pioglitazone data that were presented at that time because they were pretty preliminary. I was much more persuaded this time, including Dr. Graham's analysis. I feel that pioglitazone is a perfectly acceptable alternative.

DR. SAVAGE: Peter Savage. I voted D (keep on the market with restrictions) I was also oscillating between D and E because I think that the evidence of potential harm associated with rosiglitazone is stronger now than it was in 2007. And very importantly, the evidence about pioglitazone is substantially greater than what we saw treat in 2007.

DR. FLEMING: Fleming. I voted E. My main sense about this is really explained in my answer to question number 7. There's very concerning data about safety with rosiglitazone. It's not definitive, but if TIDE is to provide that, we have many years before we're going to get that insight. We do have an alternative, pioglitazone, for which there is considerably strong safety experience. So I come down to, then, what is the continued role for rosiglitazone?

DR. THOMAS: Abraham Thomas. I voted E. The scientist in me says we should always seek the truth. But this isn't an NIH study section. This isn't the review of a journal for publication. Really, what this is is an intersection, as someone mentioned at lunch, between public policy and science. And when we look at it that way, we can't always have the absolute truth to make a decision. We have other classes that are available that we never had before for the treatment of diabetes. And if rosiglitazone was removed from the market, we still have another TZD, what has had a trial that does demonstrate no increased cardiovascular mortality, no increased cardiovascular events, in PROactive.

Wednesday, June 8, 2011

Don't Take High Dose Simvastatin!

The current recommendation is not to start simvastatin at 80mg and only to continue taking the 80mg if you "have been taking this dose for 12 months or more and have not experienced any muscle toxicity. It should not be prescribed to new patients.

In fact, simvastatin makes sense for many patients. Most data suggest that benefit is derived from statins when they reach about a 30% reduction in bad cholesterol, or LDL. The folks at the NIH's NHLBI have evaluated the efficacy of all the available statins (see below) and you can see that most statins will achieve that goal at various doses. For example 10mg of atorvastatin (Lipitor), 20-40mg of simvastatin, and 5mg of rosuvastatin (Crestor) all lower LDL cholesterol by about the same amount. Thus, if you just need a 30% reduction in LDL, you should be fine with the generic. Problem is that many patients need more than that amount of reduction. Thus, if you want to stick to a generic, you would have to go to 80mg of simvastatin.

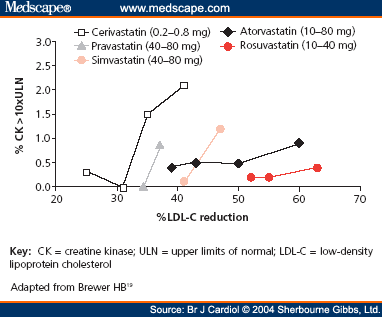

Now one might thing that the stronger, more potent the statin, the more likely it is to cause side effects. Turns out the opposite is true. The graph below shows that when plotting LDL reduction against number of patients developing myopathy (what the FDA is concerned about), it seems like the more potent statins (Crestor, Lipitor) not only lower cholesterol better, but have a lower risk of myopathy. Myopathy is pretty uncommon, usually only about 1/10,000 or 0.01%. Looking at both Lipitor and Crestor, you can see as the dose goes up (10, 20, 40, 80) the percent of reduction of LDL continues to improve, but rate of myopathy is pretty much the same except for a slight bump at the 80mg dose of Lipitor. (Though not on the graph, you can see why the 80 mg dose of Crestor wasn't approved, because at that dose there was significant myopathy). However, when you jump from 40-80 mg of simvastatin, the LDL only goes up a few points, but the rate of myopathy skyrockets to over 1% (that's 1/100 instead of 1/10,000). Finally, you can why cerivastatin or Baycol was pulled from the market. It was pretty weak at lowering LDL, but had up to 2% incidence of myopathy at the higher doses.

The good news is that Lipitor will go generic in only a few months. When that happens, I am sure that the graph above will change drastically. All Lipitor scripts will likely go to the generic medication and probably many of the simvastatin prescriptions will also switch to generic atorvastin, since it is a better statin (more potent, fewer side effects). Crestor is another option (most effective, fewest side effects), but will not go generic for a while. The other thing to note is that Pfizer, who is about to lose Lipitor, is trying to get as much business as it can by offering patient coupons, so that (as long as you are not on Medicare part D or Medicaid) a prescription of Lipitor will only cost you $4 until it goes generic.

Bottom Line: All statins are not created equal and generic is not always best. If you are on Simvastatin 80mg, you should seriously discuss with your doctor about switching. In fact, if you are on simvastatin at any dose and not on Medicare part D or Medicaid, but have commercial insurance, you should consider asking your doctor about switching to Lipitor with the $4 coupon (you may actually save money by NOT taking the generic) until it too goes generic.

Saturday, June 4, 2011

What to do about Niacin?

One of the main points of from these findings is that we have to be careful when it comes to using surrogate endpoints (like LDL and HDL) for treatment. For example, lowering the LDL with a statin reduces heart attacks and strokes. However, lowering the LDL with ezetimibe (Zetia) doesn't seem to do this (see here for more details) This might be the case for Niacin and HDL as well.

I have never been a big fan of Niacin because it causes pretty bad flushing, increases uric acid/gout, and most importantly raises blood glucose. Most of my patients are diabetic/prediabetic, so raising their blood sugar is not something I am too fond of. The other drugs that can raise HDL and lower triglycerides are fibrates. Gemfibrozil has clearly demonstrated this in a large VA study (VA-HIT). The problem with gemfibrozil is that it can interact with statins, causing some serious side effects. Statins are the one med that clearly works in just about everyone with increased cardiac risk. Fenofibrate works the same way, but can be used safely with a statin. However, when they tried to demonstrate cardiovascular improvements with fenofibrate (FIELD study), the primary outcome was not statistically significant. One of the differences between VA-HIT and FIELD is that more patients were on statins in FIELD, since FIELD was a more recent study and regular use of statins had become standard of care. However, in the diabetic patients with low HDL and high triglycerides, the FIELD study did show that fenofibrate reduced heart attacks and strokes. The ACCORD lipid study (another large, randomized, NIH sponsored trial), attempted to prove benefit by adding fenofibrate to all diabetics on a statin, but failed. However, similar to FIELD, in those diabetics with low HDL and high triglycerides, fenofibrate added to a statin did reduce heart attacks and strokes. The consistency of these findings therefore have some merit.

Bottom Line: Statins remain the first choice for patients at increased cardiovascular risk and should be used at doses that meet individual LDL goals and/or lower LDL by 30-40%. After that, the rationale for treating low HDL/high trigs is now less clear. Before we see the actual data from the AIM-HIGH study, it would be premature to pull all patients off of Niacin. That being said, in my opinion, Niacin's days are likely numbered. Evidence for raising HDL and lowering triglycerides seems to be much stronger for fenofibrate, at least in diabetics, and fenofibrate does not seem to have the negative effects, specifically hyperglycemia, seen with Niacin.

Sunday, May 29, 2011

Metformin is first, but what diabetes medicine is #2?

For a more complete discussion, see my Medscape blog post "Metformin is first, but what diabetes medicine should be your second choice?" (You will need to create a log in and password for Medscape in order to see this).

Sunday, May 15, 2011

Time to Get Together on Reducing Health Care Costs

"The latest Milliman Medical Index, which measures the total cost of health care for a typical family of four covered by a preferred provider plan (PPO), rose 7.3% to $19,393 in 2011. The per-employee cost more than doubled between 2002 and 2011. And the employee’s share of that cost now stands at 39.7%."

In other words, escalating health care costs are destroying business in America making an economic recovery almost impossible and the health safety net for our senior citizens (which working non-seniors currently pay for) will shortly disappear.

We can argue whether or not heath care in America should be entirely government run or completely private. We can argue whether health care is a right for our citizens or an entitlement we can't afford. However, reducing the escalating cost of health care should be something both sides can come together on.

An editorial in today's Washington Post looks to where President Obama and Mr. Ryan could possibly come together:

"The current debate has an ideological incoherence on both sides. Republicans endorse a premium support model for Medicare even as they work to undo the new insurance exchanges in the health-care law. Democrats distrust premium support when it comes to Medicare but support the exchanges, with sliding scale subsidies that amount to premium support, in the health-care plan. The problem of getting health-care costs under control is complicated enough without knee-jerk opposition being the default reaction to any proposal from the other side."

Given that the 2012 elections are not far away, it is unlikely that there will be any common ground seeking in the near future. However, our country can not wait much longer for politicians to put away their partisanship and come together on the one thing that both sides can and should agree on: we are spending too much money on health care and it is bankrupting the country.

Monday, May 9, 2011

May is National Women's Health Week

5 Ways to Take Control of Your Health During May Women’s Health Week

1. There’s a Doctor in the House. This month, schedule an appointment with your health care professional to receive your regular checkups and preventive screenings. The new health care reform legislation requires new health plans to cover recommended preventive services, including mammograms, colonoscopies, immunizations, and well-baby and well-child screenings without charging deductibles, co-payments, or co-insurance. It also assures women the right to see an OB/GYN without having to obtain a referral first. To learn more about the new benefits and cost savings available, please visit http://www.healthcare.gov/.

2. Move! Exercise is critical to staying healthy and managing chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension and arthritis pain. And, exercise can help prevent more serious complications, such as diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) in diabetics. With the responsibilities of work and family, it’s understandable that it might seem impossible to find the time and motivation to get moving. But physical activity can be as simple as taking the stairs, taking a walk at lunch with coworkers, setting a good example for your family by playing with your children outside, or going dancing with friends or family.

3. "Winning" by unwinding. Many women feel heavy stress from health, economic, and family issues, including health problems of their family members, financial concerns, and career challenges. Mental health is an often overlooked but critical aspect of women’s health care. Pay attention to your mental health, including getting enough sleep and managing stress to help prevent chronic disease. Take some “me time” to relax and meditate. Give yourself a pat on the back for taking steps to better health.

4. Food for Thought. An important factor in preventing chronic diseases is to maintain a healthy weight. Eating a balanced diet high in fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean protein and dairy, and “good fat” is easier than think. Eating right for you also sets a good example for your family.

5. No Smoking! Avoid risky behaviors, such as smoking. Speak with your health care provider and your employer about benefits and resources available to help you quit like the one available to Federal Employees and retirees

Friday, April 1, 2011

Using Actos to Prevent Diabetes

The NEJM study randomized over 600 patient who were at high risk for developing diabetes to pioglitazone (Actos) or placebo and found that after about 2.5 years, 2.1% in the pioglitazone group and 7.6% in the placebo group progressed to diabetes (which is a relative 72% risk reduction). On the down side, patients on pioglitazone gained about 7 pounds more and about 7% more had edema.

To assess the value of using TZD's like Actos to prevent diabetes, it is important to understand what diabetes really is, how it is defined, and why TZD's might be a very important option despite the associated risks. Unlike type 1 diabetes which is mostly about the destruction of the beta cells in the pancreas and subsequent lack of insulin, type 2 diabetes is a long process that is about much more than blood sugar. Type 2 diabetes is a result of genetic factors that control how individuals utilize glucose, about age, and about obesity. These factors combine to cause much more than just the body's impaired ability to utilize sugar. There is increased inflammation, worsening of cholesterol, increased blood pressure and increased blood clotting, just to name a few. All of these factors, including elevated sugar, combine over years and years to increase the risk of microvascular complications (eye, kidney, nerves) and macrovascular complications (heart attack and stroke). The process occurs for many years, and it is estimated that at the time of diagnosis of diabetes, the process (let's call it metabolic syndrome) has been going on for about a decade and that about half of the pancreas' function is lost despite having relatively high levels of insulin. Men who meet the diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome have three times the risk of heart attack and stroke and women who meet this criteria have six times the risk.

When we call a diabetic a diabetic is quite arbitrary. The guidelines used to classify diabetes as a fasting glucose of 140. This was lowered several years ago to 126 recognizing that complications were occurring at sugar levels lower than 140, and the cut off of 140 was too high because it was delaying treatment. More recently, in 2010 the ADA recommended that diabetes be diagnosed at a hemoglobin A1c of 6.5% or greater, recognizing a fasting glucose of 126 missed many of the diabetics with impaired post-prandial glucose, thus leading to possible delays in therapy. In fact, based on this new criteria, some of the patients in the Actos study who were not classified as having diabetes, would now be called diabetics. It is not inconceivable in the near future, that the threshold for diagnosis and treatment of diabetes occurs at an even lower fasting glucose number, A1c, or some constellation of markers. In other words, whether or not we are really preventing diabetes or just delaying the time to reach an arbitrary threshold is more of semantics. The bottom line is that in patients with impaired fasting glucose, there is an underlying disease process leading to complications that ought to be addressed.

To make an informed decision, one has to review the three main studies that looked at drugs for the "prevention" of diabetes. The study above for Actos, was very similar in design and findings to the other TZD rosiglitazone or Avandia called the DREAM study. The other major study, called the Diabetes Prevention Program (or DPP) looked at metformin vs. diet and exercise vs. placebo. Interestingly, diet and exercise beat metformin for preventing diabetes. Why would this be? It has to do with the fact that diet and exercise reverses the process of insulin resistance whereas metformin merely lowers blood sugar. Metformin was not included in the rosi or pioglitazone studies, nor was there a diet and exercise arm, so it is hard to compare all three interventions (diet/exercise, metformin, TZD) in preventing diabetes complared to placebo. However, troglitazone, an early TZD which was pulled from the market for liver complications (Actos and Avandia have not shown these problems) was initially used in the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), but was stopped after less than a year. Interestingly, in that short time, troglitazone did better than both metformin and diet and exercise. In other words, when you address insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome either by diet and exercise or with a TZD, you prevent diabetes much better than with a drug like metformin that only addresses blood sugar or placebo. This is important because the Actos study not only showed decreased rates of diabetes, but also showed statistically significant decreases in blood pressure, plaque build up, and increases in HDL or good cholesterol.

This begs the question, if you can prevent diabetes (or treat the underlying process that has not yet met the arbitrary criteria to be called diabetes) with Actos or lifestyle modications, why would you choose a drug? The answer is that lifestyle modifications is always preferred, but often not practical or easy to do. For the lifestyle intervention group in the DPP, participants were instructed to limit their calories to 1200-1800, get 150 minutes of exercise a week, had 16 sessions of counselling, and access to nutritionists, personal trainers, and behavioral counsellors. Another way to look at this is that anyone can go on "The Biggest Loser" and lose weight if they are given that amount of support (and time to take off from work), but this is not always practical. Interestingly, much of this support is not covered by traditional health insurance (where medication is), and once could argue that this is where we ought to devote our precious health care dollars (topic for another post).

As a physician, I need to help my patient the best way I can. I need to be practical. For all patients, diet and exercise is clearly the first step and always encouraged at every step. However, practically speaking, this just doesn't work all the time. It takes a highly motivated patient with a lot of resources and support to do this. Thus, if I can use a medication that will help reverse the underlying disease process of insulin resistance and delay the diagnosis of overt diabetes (along with diet and exercise), then I believe I am ethically obligated to do so.

Finally, the big issue that has been brought up is side effects. Mainly weight gain and heart failure. First, the TZD's do not "cause" heart failure. What I mean by this is that Actos has no direct effect on the heart. What is does do is increase fluid retention. For patients whose hearts are not working that great (pre-heart failure), a little extra fluid can push them into heart failure. Though this is a serious risk, it is not that common and can be addressed by carefully monitoring patients before and after treatment. Secondly, weight gain is a real issue. There are two components of weight gain caused by TZD's. The first is the aforementioned fluid retention. The second has to do with reversing the underlying disease process. Patients with diabetes and metabolic syndrome do not utilize glucose correctly. This causes subsequent increases in insulin and eventual pancreas failure leading to the need (over years) of supplemental insulin. By not using sugar, weight is not gained. By correcting the process, the sugar goes to where it is supposed to, which leads to weight gain. However, it is not clear that this weight gain is necessarily "bad." Studies show that TZD treated patients shift their fat from the dangerous visceral abdominal fat (associated with high cardiovascular risk) to more centralized fat stores. In other words, though not proven by a randomized control trial, reversing the disease process (glucose, cholesterol, blood pressure, weight gain) is likely to prevent more adverse events (heart attack and stroke) then events caused by additional weight.

Bottom line: Obesity is an epidemic in our country and will soon be the single leading cause of preventable death in the US. Along with obesity comes diabetes, which takes years to develop and is defined by arbitrary criteria. This diease process (metabolic syndrome) is associated with it's own consequences. Diet and exercise leading to subsequent weight loss and improved cardiovascular health is clearly the best choice. However, for most patients for very practical reasons, this method is not successful. Until there are changes to our health care system and/or public health initiatives that make intense lifestyle modifications more reasonable, pharmacotherapy to prevent diabetes has an important role. Pioglitazone has demonstrated that it can effectively prevent diabetes in most patients with known but manageable side effects, and therefore should be considered a useful tool.

Friday, March 18, 2011

Good Bye Primatene Mist

This is because, similar to the old albuterol meter dose inhalers, Primatene Mist uses a CFC as a propellant which is harmful to the environment. I blogged about this previously (see FDA Announces End for CFC-Propelled Inhalers Asthma inhalers and More on Asthma Inhalers ).

However, the loss of Primatene Mist is a good thing in my opinion. Primatene Mist is epinephrine. It is a bronchodilator, which is why it relieves the symptoms of asthma. However, it is quite dangerous, especially without a prescription. First, it is not just a beta 2 agonist like albuterol which works almost exclusively on beta receptors in the lungs. It also aftects beta 1 receptors in the heart and alpha receptors in the blood vessels. The primary use of epinephrine is medicine today is to give it to patients who are a risk of immediate death in order to restart their hearts. In addition, having any bronchodilator, even albuterol, over the counter, is a bad thing. We know that increased albuterol use is associated with increased ER visits, hospitalizations and even death. But at least we can monitor albuterol use, because it must be prescribed by a physician. We have no way of knowing if a patient is taking too much Primatene mist until they are dead.

Under a physician's supervision, with a proper asthma plan and additional chronic maintenance medications for asthma, such as inhaled corticosteroids, bronchodilators can be used safely and effectively. However, over-use of these medications especially in the absence of inhaled corticosteroids is dangerous. This is why I never write an albuterol prescription with any refills. If your asthma is well controlled, one albuterol inhaler should last you a year and you shouldn't need refills. If you are refilling the albuterol more than one time in a year, by the NIH's criteria, your asthma is not under control and you may need to change to a stronger daily medication (for example, switch from Singulair to an inhaled corticosteroid or ICS, or switch from an ICS to an ICS/LABA combination).

For those patients without prescription insurance who relied on the relatively low cost of OTC Primatene mist, be advised the GSK makes a sample size of Ventolin HFA (60 inhalations) that is only $9 out of pocket (regardless of insurance) at most major retail pharmacies. This will of course require a doctor's prescrition, but I believe that is a good thing for the reasons stated above.

Thursday, March 17, 2011

2011 Residency Match NOT Good News for Primary Care

Don't believe the hype.

This was not a good match for primary care or our health care system in general. These positive reports are based on the press release from the National Resident Matching Program or NRMP which is the group that runs the match. They stated that

"The number of U.S. seniors matched to family medicine positions rose by 11 percent over 2010 . Among primary care specialties, family medicine programs continued to experience the strongest growth in the number of positions filled by U.S. seniors. In this year’s Match, U.S. seniors filled nearly half of the 2,708 family medicine residency slots. Family medicine also offered 100 more positions this year.

The two other primary care specialties that increased in popularity among U.S. seniors were pediatrics and internal medicine. U.S. seniors matched to 1,768 of the 2,482 pediatric positions offered, a 3 percent increase over 2010. In internal medicine, U.S. seniors filled 2, 940 of 5,121 positions, an 8 percent increase over last year."

At first glance, this seems like good news for primary care. However, their use of statistics is misleading. They are not taking into account that there were almost 500 more US medical students in the match this year. This is equivalent to a drug company telling you that their medication reduces hearts attacks by 30% (from 50 to 35), but forgets to tell you that there were 1000 patients in each group, so that the real reduction in heart attacks is only 1.5%.

What you need to look at is the percent of US medical students that matched into that speciality and whether or not it changed from last year to this year. If you go to the NRMP web site, you can get the actual raw numbers. For Pediatrics, though more US seniors matched into Pediatric residencies (remember there was about 500 more students this year than last), the percent of US seniors matching into Pediatrics was unchanged. For Family Medicine, there was a slight bump, but compared to last year, only about 1/2 of a percent more of US seniors chose to go into Family Medicine (far less impressive than the relative increase of 11%). The real big bump was in Internal Medicine, where almost 1% more US seniors matched into Internal Medicine. However, we know from previous studies, that only 2% of seniors that choose Internal Medicine plan to go into primary care. (See here for previous post).

What is also in the NRMP press release (that some are paying less attention to)

"Dermatology, orthopaedic surgery, otolaryngology, plastic surgery, radiation oncology, thoracic surgery, and vascular surgery were the most competitive fields for applicants. At least 90 percent of those positions were filled by U.S. medical school seniors.

The number of U.S. medical school seniors in emergency medicine increased by 7 percent and grew for the sixth year in a row, as they filled 1,268 of the 1,607 first-year positions available. Anesthesiology offered 44 more positions and matched 45 more U.S. seniors who filled 671 positions of the 841 offered "

Essentially, though there are more medical students this year than last, and thus more doctors available to society when they are done with their residencies, the same low numbers of students are choosing residencies that will lead to careers in primary care. This small increase will not make up for the many patients in the US who lack a primary care physicians and certainly won't even begin to fill the gap when many of our now close to 50 million uninsured patients suddenly gain insurance under health care reform. Rather, despite the clear need for more primary care physicians, our students continue to choose the more lucrative subspecialties.

America, this is a crisis. Many of the few primary care docs we have are retiring, leaving practice, or going cash only or retainer. Our students see this and continue to choose other specialties. If something is not done to increase the value, reimbursement, and job satisfaction of our primary care doctors; we will have no one left to care for our sick and aging population. (And before you post a comment about NP's and PA's filling this gap, those students aren't going into primary care either. A surgical PA makes more money than a primary care MD).